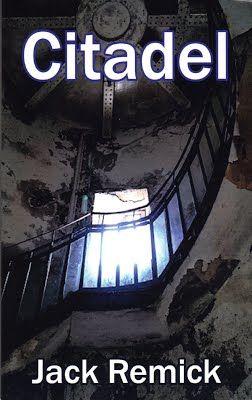

Women’s literary fiction

Publisher: Quartet Global Books

Irven DeVore, an evolutionary biologist, writes that "Males are a breeding experiment run by females." What if, in fact, women ran everything? What if women rejected the culture of rape and violence to take control of their lives in the safety of the Citadels? What if women could exist without males? CITADEL is a metafictional, apocalyptic story braided into a contemporary post-lesbian novel built on genetics.

Advance Praise

"I loved the book and I'm suggesting it to all the writers, editors and women I know as a must read. You blew me away... the book drew me in completely... great experience!

I'm not sure how you managed to come up with this... let alone research it... a story usually follows one or two Characters... I found myself following the writer, the editor, the publisher, not to mention the Characters in the book... and never got lost, never ended up wondering who someone was or why they did that? I read the book in short spurts and longer chunks depending on opportunity... but never had a problem of falling back into the story... you had me from page one to the end. Great job" -- Wally Lane, filmmaker, screenwriter.

Interview

Is There a Message in Your Novel That You Want

Readers to Grasp?

Yes.

More than anything, I want readers to see what the world would look like if

women ran it. Irven DeVore, an evolutionary biologist, writes that “males are a

breeding experiment run by females.” That insight opens up huge gaps in the

notion that the white, Alpha male is somehow a privileged being just because he

can carry an AR 15 and tattoo a swastika on his forehead. I want the female readers

to shed their fear and take on the world. In short—to resist. I want the female

readers to understand that they don’t need the Y chromosome to be entire and

intact. In Citadel, I incorporate a scientific concept called

ICNI—Intracytoplasmic Nuclear Injection. This is a process whereby women can

become pregnant without the 23 chromosomes on the Y. That idea itself is

terrifying to men but can give women some comfort in knowing that if they

reject the Y, they can still live full, rich lives with love and caring free of

the horrors the Y chromosome, as it’s engendered in the blood-thirsty male, unleashes

on the world. There is a scene in Citadel where the Daughters (all the female

characters in Citadel are Daughters because of the genetic truth that all cells

are daughter cells) make an excursion into the residual male world where they

discover men who live like women once lived, and they are horrified.

Is there anything you find particularly

challenging in your writing?

When

I look at Citadel now, I see some major challenges to male readers. I don’t

expect many male readers because of the nature of the novel. In Citadel, there

is a section called The Focus Group. In that section, the women react to their

readings of the pre-publication novel and their reactions are as close as I

come to actual realism—which I do not like at all because it limits our minds

and our story telling. In the Focus Group, several of the women readers report

back that they know exactly what the author is getting at because, “that is my

story,” they say. “It’s like the author is reading my mind. Has she been raped?

I know she has to have been raped.” When

men read Citadel, and they come to the Focus Group, there are some powerful

reactions because the finger points directly at them and they feel the terror

that their own white male privilege gives them.

How many books have you written and which is your

favorite?

I

have written twenty books. These include novels, poetry, short stories,

screenplays, and non-fiction. Asking me which of those works is my favorite is

like asking which of my eyes is my favorite. Impossible to answer the question

because each of my novels approaches the human condition from a different

angle. Citadel looks at a world where women control everything; Gabriela and

The Widow takes on the question of being a female immigrant. Lemon Custard asks

what happens to a young mother who abandons her children. Blood tackles the

prison system and its insanity while The Deification shows us the second Beat

Generation in action as the main character journeys to San Francisco on a quest

to become a poet. Valley Boy works a young Okie’s life from field hand to

college student. Because each of the novels puts some aspect of the American

experience under scrutiny, I think that an overview of the novels, and the

poetry, suggest something about the culture we live in. I am an American writer

exploring the peculiar reality of being a writer in a society that does not

really value writers.

If You had the chance to cast your main character

from Hollywood

Tough question. The Hollywood/Indie

world is in such flux that even were I to suggest an actor, by the time the

script came online, that person would probably already be out of the frame.

When did you begin writing?

Serious

writing didn’t begin until I worked with Natalie Goldberg a few times. Until

then, I was lost in a kind of ultra-sophisticated wasteland without vision or

form. After I discovered timed writing, what NG calls “writing practice”, my

vision changed. As a result, I found a way into fiction that had been denied to

me before. Following my mind, as Goldberg says, led me to a deeper

understanding of what writing is all about—freeing the inner vision from the

internal editor. Self-criticism and self-loathing are these gigantic roadblocks

that have to be overcome if the writer is to find the singular path to

creativity. For me, the confluence of NG’s timed writing and some time spent

with a very enlightened Jungian psychologist allowed me to quit writing the

same story over and over and to branch out into a world of possible universes.

Each work grows out of the previous one by adding technique, ideas, and

organized research to ride along with the creative vision. For me, I can say that

everything after Blood and leading up to Citadel is a prelude or a pretext or a

practice. Only when the writer finds a way to put the Ego aside, does the

vision complete itself. This is a Zen/Buddhist concept that finds workability

in the real world if you, the writer, pay attention. Attentiveness is primary

if you are to understand that in each story, there are really three: Story One

is the story your Ego wants credit for; Story Two is the story that begs, even

demands that you write it; Story Three is the story your readers want you to

write. If you write Story Three, you are a slave to taste, tradition and a

victim of expectation. That leaves Story Two as the real writing. The deep

writing. The writing that takes you out of the Ego and into another world. For

me, that Story is Citadel.

How long did it take to complete your first book?

There

are two questions here: the first book and the first published book. My first

published novel is called The Stolen House. It grew out of my early writing in

which experimentation was very big. I wrote it at a time when the underground

magazines were in full bloom. There were small press magazines all over the

world hungry for new material that didn’t pay homage to what had gone before.

It was a time of the great freedom seekers and the time of the early feminist

presses looking beyond the patriarchy for new ideas and expressions. Following

the publication of The Stolen House, I wrote many novels that are still on my

writing room shelf. The next book, one that I spent years on, is called

Terminal Weird. It is a book of short stories. Later, I co-wrote The Weekend

Novelist Writes a Mystery—my first non-fiction success—with Robert J. Ray. That

began a long and productive association with Ray and led finally to the series

of novels that Catherine Treadgold at Coffeetown Press published—Blood;

Gabriela and The Widow: The California Quartet.

Did you have an author who inspired you to become

a writer?

This

is a difficult question to answer because the exact moment I decided to write

something beyond letters and graffiti is still a mystery. I do remember reading

as far afield as I could—in Russian, French, Spanish, Italian—as if knowing

what was going on in the minds of other writers was very important. So often I

see writers taken in by the mind of a successful author and using that either

as a model for their own early work or imitating it in a betrayal of their own

beautiful and possible creations. In the Zen world, the saying is well

known—the student must surpass the master or there is no progress. If we look

back at the authors who might have inspired us, we often come face to face with

our own shortcomings in thinking that those authors were the only masters we

could and should imitate. I ask you to read Madame de Stael or James Fennimore

Cooper and then tell me that that is the writing you want to do. The progress

is evident. We are in a new and exciting place with writing. We don’t know

where the electronic world will take us, but we can be certain it will not be back

to the Old Style.

What is your favorite part of the writing

process?

The early writing, what I call

“writing about the writing.” Say I have an idea but it’s not developed. Instead

of digging into the novel and writing discovery work, I stand back and ask

questions about what is going on. I write about the writing. For example,

Citadel, the Outer novel (Citadel is a novel within a novel. The Outer novel

has no name, but tracks the relationship of Trisha, an editor, and Daiva, a

novelist) began with some writing about a character—no name yet—in a motel in

the desert. Why is she there? What does she look like? Long before I wrote a

single scene in the Outer novel, I had three hundred pages of writing about the

writing. Once that is done, and I know what the story is, know who the

characters are and where they came from, it is on to the scenes. And each scene

then has meaning and depth because of the texture of the writing about the

writing. When I taught I a screenwriting program, I knew writers who wrote

several hundred page “treatments” before they took on the screenplay itself.

Writing about the writing has to be the most satisfying part of writing apart

from finishing the novel. I am fond of saying that writers have just three

problems—How to start; how to keep going; how to finish. If you solve those

problems, you have it licked. But this is paramount—Always finish. Always.

Finish.

Describe your latest book in 4 words.

Post-lesbian

apocalyptic metafiction

Can you share a little bit about your current

work or what is in the future for your writing?

After

finishing Citadel, I began work on a collection of essays titled: What Do I

Know? Wisdom in the Twenty-first Century. Although this book is still in

manuscript, I have published five of the essays. This is a departure for me,

because I do not like to send out excerpts. Excerpts I see as trial balloons.

To solve the problem of the trial balloon, I work with other writers on a

weekly basis. We sit around a table, read work in progress, listen to one

another, then go back for the rewrite. Rewriting is a terribly undervalued

process for most writers. I will continue this process until What Do I Know is

finished.

About the Author

Jack Remick is the author of twenty books—novels, poetry, short stories, screenplays. He co-authored The Weekend Novelist Writes a Mystery with Robert J. Ray. His novel Gabriela and The Widow was a finalist for the Montaigne Medal as well as a finalist in Foreword Magazine’s Book of the Year Award. He reviews for the New York Journal of Books. He is a frequent guest and co-host on Michigan Avenue Media with Marsha Casper Cook. His novel Citadel, was featured in the July issue of the Australian magazine eYs.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

0 Comments